Navigating Rootlessness and Being a Beginner

JASMINE YADAV

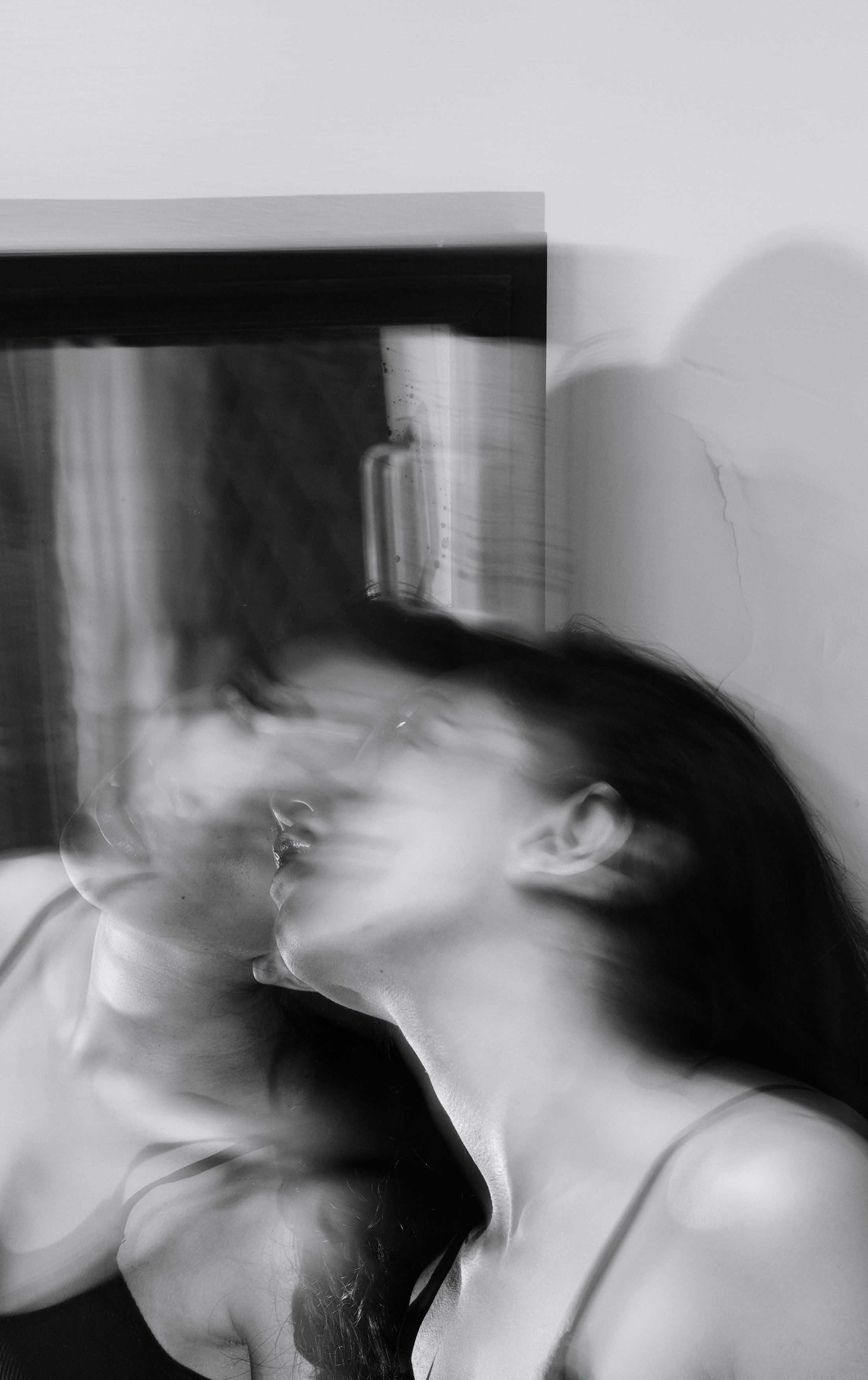

Photos: Venus Maku Thokchom

Prompting and provoking the body.

A learning, un-learning body. A fearful, broken-record, posture-correcting, back-aching body. A willing, creature body. A whispering, reluctant, machine body. slipping

falling

demanding

silent

still

loud

obnoxious

careful

careless body. A dancer’s body. A rooted body... A..

.

.

R

O

O

T

L

E

S

S body. A body.

This essay breathes through some of (my) ‘doing’ and ‘not-doing’ since the first lockdown, and some questions that arose since then. It explores what is uncomfortable and describes the slow, deliberate shifts in the ways the body now dances, makes dance and approaches form. The writing also offers the reader some movements and pauses in the form of prompts and questions, in an attempt to allow dance to infect these words OR

…to find new ways of articulating that invite or encourage dance.

The images are of a dancing creature moving, resting and breathing in the space of her bedroom. There is lingering in the scattered thoughts and ideas that came up as a result of experiencing isolation, a lost sense of time, rejection and hopelessness. There is collapse and a remembering of the ‘lasts’. There is stuckness, wonder, a ghost-like existence and also nothingness.

Finding Form: failure, fall and getting lost

Everything I believed to be true of artistic practice got completely shaken up in March 2020 as we experienced the global pandemic and sat in our homes through multiple lockdowns. The body was used to travelling long distances and it longed for movement, proximity, intimacy and connection with others.

”Sometimes it is difficult to find a reason to still dance.”

“I am struggling to do anything!!!”

“How does one begin again?”

These are lines I pulled out from a text exchange with a close friend who is a dancer.

During this time, I was forced to return to a key question: what makes up a ‘practice’? How do we acknowledge practice that once lived and thrived in a body but doesn’t anymore? How do we plot and trace what is left of our ‘practice’ in our bodies? What has the body held on to in terms of practice? Is there a discomfort with, or an acceptance of what a practice has become?

The ways in which our bodies mould, hold shape and space, have everything to do with our social, political, economic and cultural environment and lifestyle. Dancers have the unique advantage/ disadvantage of manipulating this and of allowing the body to visit multiple ways of creating/taking shape. But often, in these attempts, there can be a distance from what is felt and sensed; more emphasis is laid on how the body looks, what is seen and made visible. Since the pandemic struck, I found myself being more playful, more stuck, more experimentative, but also deeply uncomfortable with my practice of dance. I noticed a strong urge to correct. I noticed polarity, extreme states of doing and not-doing. These looked at times like panicky confrontations, or complete collapse, detachment and exhaustion.

Over the last few months (of the 2021 lockdown), I started to talk to myself out loud. I was inspired by Bill T. Jones' performance: “Breathing Show”. In this he performs a dance phrase in four phases. In the first phase the movement phrase is simply performed. In the second phase, he performs the phrase as though he is teaching a class, describing verbally exactly what he is doing with as much detail as possible. In the third phase, he performs the phrase as clearly as he can, but this time he says whatever he is thinking or feeling out loud as he performs the material. He speaks without filtering or censoring while keeping the movement as accurate as possible. In phase four, what he says affects what he does, and what he does affects what he is thinking and what he says.

This step-by-step breaking away from structured choreography opens up a lot of inner dialogue. What do we feel/think about the material we are performing? It becomes a display of what kind of thoughts and sounds movement generates, and how thoughts and words provoke movement. This format brings inner conflicts to surface. It exposes the psyche, memories and vulnerable moments that make up the complex dancing creatures that we are. As Jones performs the third and fourth phases he throws words like “beautiful beautiful ballet dancer, Pina Bausch, roll through.. Don’t criticise.” Sometimes his voice explodes in a scream.

As I entered a similar exploration of a single dance phrase in four phases, I started to become aware of and reveal the internal dilemmas and conflicts of the material I was performing. The body passed through forms and institutions that continue to live in and choreograph the body. Words slipped out in songs, whispers, and loud gasps.

Phases 2, 3 and 4 of one such exploration are described below:

## Legs bend in a deep, open squat. Hands reach the back of the head, fingers interlock. The weight of the hands pushes the head down. The body falls on the ground. Palms find the ground, one leg sweeps the floor. This movement travels through the body and reaches the top of the head. Repeat three times. Hands land on pelvis, the body finds a kneeling posture. Hands rest on pelvis.

### “Tail bone pointing downwards. Melting forward, drop dead. (A song slips out briefly) Yeh mera diwanapan hai ya mohabbat ka… control the movement. Stop. breathe.”

#### “Deep squats are nice, revolve, discover, aramandi, sit deep, but extend tall.” —---------- The body bounces up and down in the squat. Legs like jelly wobble but find stillness. “Dramatic falls. Catch yourself.” The body rises and refuses to stay on the ground. Gets up and falls again and again. The floor receives the body harshly then softly. Leg sweeps the floor and a wave travels to the top of the head but this time it lasts longer. “Waves. Snakes. Mouldable body.” Hands land on either side of the pelvis moulding, pushing, pulling the pelvis as though playing with clay. Only sounds slip out in sighs, “ahhh..”

There is a crisis of form

When we learn a form, does the form also learn us?

What can and can’t I perform?

Rootlessness, Beginnings

Many dancers struggle with understanding when they are skilled enough to create their own dance pieces. The desire to create is present from day one of entering a class/training. But it is equally terrifying to be seen making a mistake or not doing a move well enough or creating something mediocre. How does the dancing body take steps away from control, caution and compliance, and move towards agency, trust, ownership and creative freedom? How do we carry this within us and break away from institutions?

Over the last few months, I have been re-entering basic dance instructions in order to discover the variety of ways in which the body can interpret a single instruction. Instructions like: “Find your neutral. Arms by your side. Drop shoulders. Roll up/down.” Although there are set ways in which the body has learnt to move, this exploration allows for failure, for doing the far-fetched things, the extra things, sometimes, the exact thing, but twisted.

Artistic agency cannot be built in one day. But creating a structure, and breaking it apart piece by piece eases the body into taking risks, surprising itself, at times disliking everything it creates, other times tapping into the body’s own archive and history. Movement language, in this way, reveals so much about who we are and what we desire. This is not to disregard an understanding of the body and movement that dance training offers. Rather, this is an invitation to expose what words invoke in the dancing body if it was not bound by the appearance of form.

Can ‘form’ be thought of as the body actively discovering movement language?

How would the meaning of creation shift if it honoured the very human experience of failure?

‘Rootlessness’ is the word I give to a practice of dance that doesn’t find a foundation in one form or philosophy of movement. Having explored a variety of movement practises, I have found myself to be a trained ‘beginner’. It is always a nervous task to enter a new class and discipline. Over the last three years, I have approached training in this way by attending short courses and crash courses. Another set of questions that have emerged for me in this time are:

What can a body that carries memories of various forms produce? What happens when movement becomes a mix or fusion of different vocabularies and approaches? What do the memories of various forms bring up in the body of the dancer? And what then are her roots or points of departure?

In a recent lecture I attended, by dancer and choreographer Pichet Klunchun, he talked of images and tradition. He spoke of how any image in itself is a tradition because it carries a memory, history and even a story. It is exciting to then look at tradition as a concept that offers possibilities rather than fixed trajectories and methods. Tradition if looked at in this regard also leaves room open for mistakes, misunderstandings, multiple interpretations or misinterpretations. I found this to be a useful tool where an image then becomes our point of departure. And even if we may not fit in a clear form or discipline, looking at our many ‘traditions’ can enable us to encounter an artistic vocabulary that is both unique and rigorous.

Our Many Homes

This experience of rootlessness also mirrors my life, growing up. Having lived in multiple cities, constantly changing homes, the question ‘how do we create, dismantle and carry our many homes?’ has been present in my thoughts for a long time. In the book ‘Species of Spaces and Other Pieces’, Perec Georges writes in the chapter “Bedroom”:

“What does it mean, to live in a room? Is to live in a place to take possession of it? What does taking possession of a place mean? As from when does somewhere become truly yours? Is it when you've put your three pairs of socks to soak in a pink plastic bowl?... Is it when you've experienced there the throes of anticipation, or the exaltations of passion, or the torments of a toothache?”

Last year, as my recovery from Covid-19 took much longer than anticipated, I grew restless, and more and more, settled into my bedroom. I had started to occupy the space in my bedroom in unusual ways. This was also the time when many of my friends and family were also Covid-positive and everyone was struggling with health, loneliness, a distorted sense of time, and profound silence. I remember how my bathroom turned into a surreal place. The body was soft and settled into the universe of the bathroom. I scribbled the following words at the time:

The creature in me is not upright

It is the living, breathing manifestation of disease

slipping

and merging into things.

What can hiding offer me?

And invisibility, passivity

and all things I deem small and unworthy?

What can getting lost offer me?

Can we turn towards what we hide away?

Shivering limbs, fragility, chaos, breath

and breathlessness?

The creature in me is not upright

It's throwing soft tantrums.

The idea of ‘home’ was very transient for my grandmother who had Alzheimer's disease. She would often confuse geographical locations. Her sense of space and time had become distorted. When we lived in Panchkula, she often thought that her home, which was in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, was just around the corner, at the next bend of the road. As care-givers, we slowly learnt not to impart facts, but instead, to offer reassurances. On arriving at her actual home in Meerut (which we had assumed was the home which was constantly referring to) where she had spent most of her life, we thought she would finally feel “at home”. The first few minutes of arriving there after several months, she looked confused. I noticed a glimmer of recognition; she was remembering something. But very soon she said, “Ghar nahi chalna kya?” (Isn’t it time to go home?) She was in constant pursuit of a home. On asking her to lead the way on one of our walks, it even became a game of chance. She thought that maybe, just maybe, on the next turn of the road she would find the home she was looking for. She would describe home with aam ke baag (mango orchard), bhains (buffalos), her childhood friend and neighbour, Chandro, sometimes her sasur (father-in-law), or dukariya (drawing room space). Sometimes she was referring to her childhood home in her village, Mandawara. Sometimes she described her sasural (husband’s home) in Dolcha.

The way I moved through the space of my home transformed drastically since the pandemic. I started to remember my grandmother, how she might have understood and configured space each time with a failing memory. I thought of her sense of space and home as I read Perec’s words:

“Space melts like sand running through one's fingers. Time bears it away and leaves me only Shapeless shreds:

To write: to try meticulously to retain something, to cause something to survive; to wrest a few precise scraps from the void as it grows, to leave somewhere a furrow, a trace, a mark or a few signs.”

Is to dance also an attempt to capture an experience and set it to time? How we settle in and choreograph our movement in spaces lies at the intersection of the real and imagined. Perec looks at “space as inventory” and “space as invention”.

Can homes be discovered, invented with the course of time?

Is home a structure, a person, a feeling,

objects or places we settle in and

pass through?

Are homes the traces we leave behind long after we’re gone?

An exercise for the reader :

Next time you find yourself lying down :-

Think about the places you have lived in and called home.

Imagine your body taking up space, growing and growing in size.

Imagine your body across a world map.

Maybe you become large enough to cover the distance between cities.

Imagine the body stretches out

to touch all the places she has been to

Your large body, only passing through.

Rolling, slipping, stretching out limbs to touch places.

What are you seeing, mapping and revealing?

Ending notes, a goodbye?

While moving and making dance we decide how we situate the body in space - whether in the centre, periphery, closer to the ground, etc. We also make decisions about how we will relate to other bodies and objects in space. How close or how far we choose to be. How much we will push the limits of the body, how fast, slow we will move, this list goes on and on. Sometimes these choices are not made and then acted upon. Sometimes one bodily movement can lead into another without thinking cerebrally. In dance, we often experience “knowing or learning” that happens through doing.

Dance urges me to ask constantly: what do we do with what we know? Of course, this question may come up in every discipline, but with dance the ground and tool for choice-making is our bodies. Therefore, the question “what do we do with what we know?” situates itself on the body.

The reason I turn towards these questions now, even as they bring up uncomfortable and uneasy thoughts, is an attempt to address this very discomfort and stuckness. Discomfort usually demands an interruption or disturbance from our scheduled programming. And maybe the places that we find ourselves stuck in can become gateways of new understandings and knowledge.

If I were to condense all the questions above into only three questions they would be:

1. Where do you and your practice belong?

2. What is your practice? OR What do you want your practice to be?

3. How do you begin?

These fairly simple questions may make it slightly easier to reflect or might further complicate matters. But the general themes all these questions carry are of belongingness, beginnings, identity and desire. The final thought I leave this essay with is, what does dance - an art practice that directly works with the body as its instrument, say about the experience of living in this body?

Movement presents itself as that f l e e t i n g home

Where the body may reside

Briefly.

Not fully welcomed

but never denied placeLiving in this home

also means leaving

Arriving and l e a v i n g

Arriving, l e a v i n g

Arriving leaving

endlessly.

References:

Breathing Show. (2008). Breathing Show - Bill T. Jones. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOSsDHLooi0&t=77s.

Chayne, K. (2021, September 16). Bayo Akomolafe speaks about slowing down and surrendering human centrality. GREEN DREAMER. Retrieved August 4, 2022, from https://greendreamer.com/podcast/dr-bayo-akomolafe-the-emergence-network

Perec, G., & Sturrock, J. (2009). Species of spaces and other pieces: Georges Perec. W. Ross MacDonald School Resource Services Library.

Jasmine Yadav is a dance practitioner with a particular interest in exploring dance as a system of care and support for the body. She is training to become a dance movement therapist. Her dance practice looks to encourage the body’s pleasure, play, risk and vulnerability. At present, she finds herself at the intersection of text and movement, investigating language around body, intimacy, consent and pleasure.